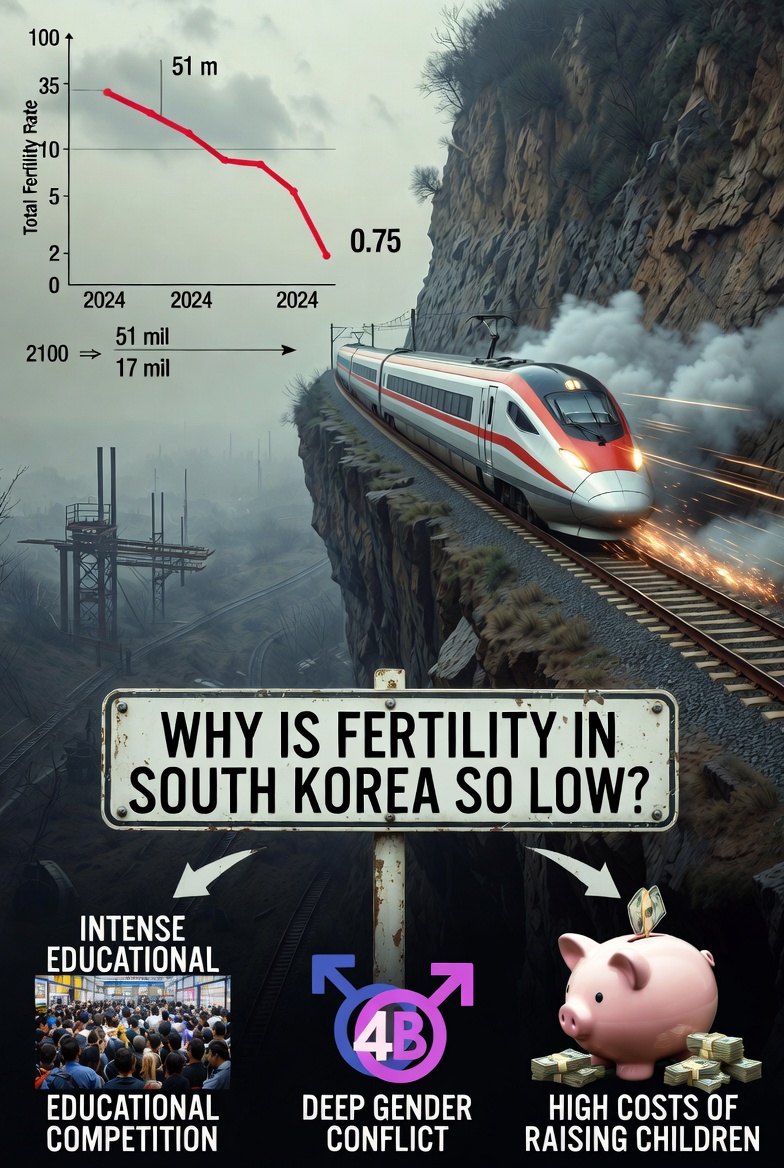

South Korea has the lowest fertility rate in the world, and the gap with other nations continues to widen. In 2024, the country's total fertility rate (TFR) stood at approximately 0.75 births per woman, according to Statistics Korea and OECD data — far below the replacement level of 2.1 needed for population stability without substantial immigration.

Preliminary estimates for 2025 suggest a slight rebound to around 0.79–0.85 in the first half of the year, driven by a modest increase in marriages and births, but the overall trend remains catastrophic.

Preliminary estimates for 2025 suggest a slight rebound to around 0.79–0.85 in the first half of the year, driven by a modest increase in marriages and births, but the overall trend remains catastrophic.

For every 100 South Koreans alive today, optimistic projections indicate only about six great-grandchildren in the next century — a stark illustration of generational collapse.

If current patterns hold, South Korea's population (51.7 million in 2025) could shrink dramatically. United Nations and national projections estimate a decline to roughly 36–47 million by 2060 and potentially as low as 15–19 million by 2100 under low-variant scenarios — a loss of more than two-thirds of the current population over the next century.

In the most pessimistic forecasts, the figure could drop to as few as 7–13 million by 2125. This rapid contraction threatens labor supply, economic growth, pension sustainability, and national defense capacity.

Intense Educational Competition and Skyrocketing Private Tutoring Costs

South Korea's hyper-competitive education system is one of the strongest deterrents to having children. Parents face immense pressure to secure their child's place in top universities, which are seen as gateways to prestigious jobs and social status. This fuels massive spending on private education (hagwon), after-school cram schools that dominate children's lives from early ages.

In 2024, total household expenditure on private education reached a record 29.2 trillion won (approximately $20.2 billion), up 60% over the past decade and marking four consecutive years of increase. Monthly spending per student averages around 410,000–611,000 won, with wealthier households and those in Seoul spending significantly more. Raising a child to age 18 is estimated to cost families hundreds of thousands of dollars — far exceeding government support — making children a financial "luxury" rather than a norm.

Gender Conflict and the Erosion of Marriage

Deep gender divides have eroded trust between young men and women, contributing to plummeting marriage rates. Women increasingly delay or forgo marriage and childbirth due to persistent inequality in domestic labor, career penalties after having children, and a male-dominated work culture with long hours. Married women often shoulder the majority of childcare and housework, even when they are breadwinners, leading many to view marriage as incompatible with personal autonomy and professional goals.

Deep gender divides have eroded trust between young men and women, contributing to plummeting marriage rates. Women increasingly delay or forgo marriage and childbirth due to persistent inequality in domestic labor, career penalties after having children, and a male-dominated work culture with long hours. Married women often shoulder the majority of childcare and housework, even when they are breadwinners, leading many to view marriage as incompatible with personal autonomy and professional goals.

Movements such as the "4B movement" — rejecting dating, marriage, sex, and childbirth — have gained traction among young women seeking independence. Meanwhile, young men face a "marriage squeeze" in which they outnumber women in the marriage market, partly due to historical son preference and current female opt-out trends. This fuels resentment, anti-feminist backlash, and further reluctance to marry.

High Opportunity Costs for Mothers and Work-Life Imbalance

Motherhood carries a severe economic penalty. By the time a child reaches age 10, many mothers lose about two-thirds of their pre-birth income due to career interruptions, part-time work, or exit from the labor force. South Korea's long working hours, rigid corporate culture, and limited affordable childcare exacerbate the dilemma. Despite generous government incentives — cash grants, monthly allowances, and parental leave — these measures have not reversed the decline, as structural barriers remain.

Historical Roots: From Anti-Natalism to Pro-Natalism

The low fertility rate is partly a legacy of aggressive state policy. In the 1960s–1980s, South Korea promoted birth control and family planning to support rapid economic growth, successfully reducing TFR from over 6 in the 1960s to below replacement by the 1980s. While effective for development, the cultural shift toward small families (or none) proved difficult to reverse once prosperity arrived and new pressures emerged.

Also read:

Also read:

- Japan's Births Plummet to Historic Low in 2025: A Demographic Crisis Deepens

- Saudi Arabia Hunts for Capital and a Place in the Future: Opening Tadawul to All Foreign Investors

- Humorless Silicon Valley and the Chinese Communist Party: Who Is Actually Building Our Future?

- Trump's Military Dirigisme: The "Dream Army" Executive Order and Free Market Nuances

A Train Speeding Toward the Cliff

South Korea resembles a high-speed train hurtling toward collapse: intense competition for limited "good" positions — elite universities, prestigious jobs, stable housing — leaves little room for family life. Everyone fights for the best seats, unaware that the driver is missing and the fuel is running out. Despite billions spent on pro-natal policies, the crisis persists because incentives cannot fully offset the costs, cultural norms, and gender tensions.

Without fundamental reforms — reducing education pressure, improving work-life balance, addressing gender equity, and potentially reconsidering immigration — South Korea faces a future of rapid aging, labor shortages, and economic strain. The country’s demographic trajectory is no longer a slow trend; it is a pressing national emergency with global lessons about the limits of growth without people.