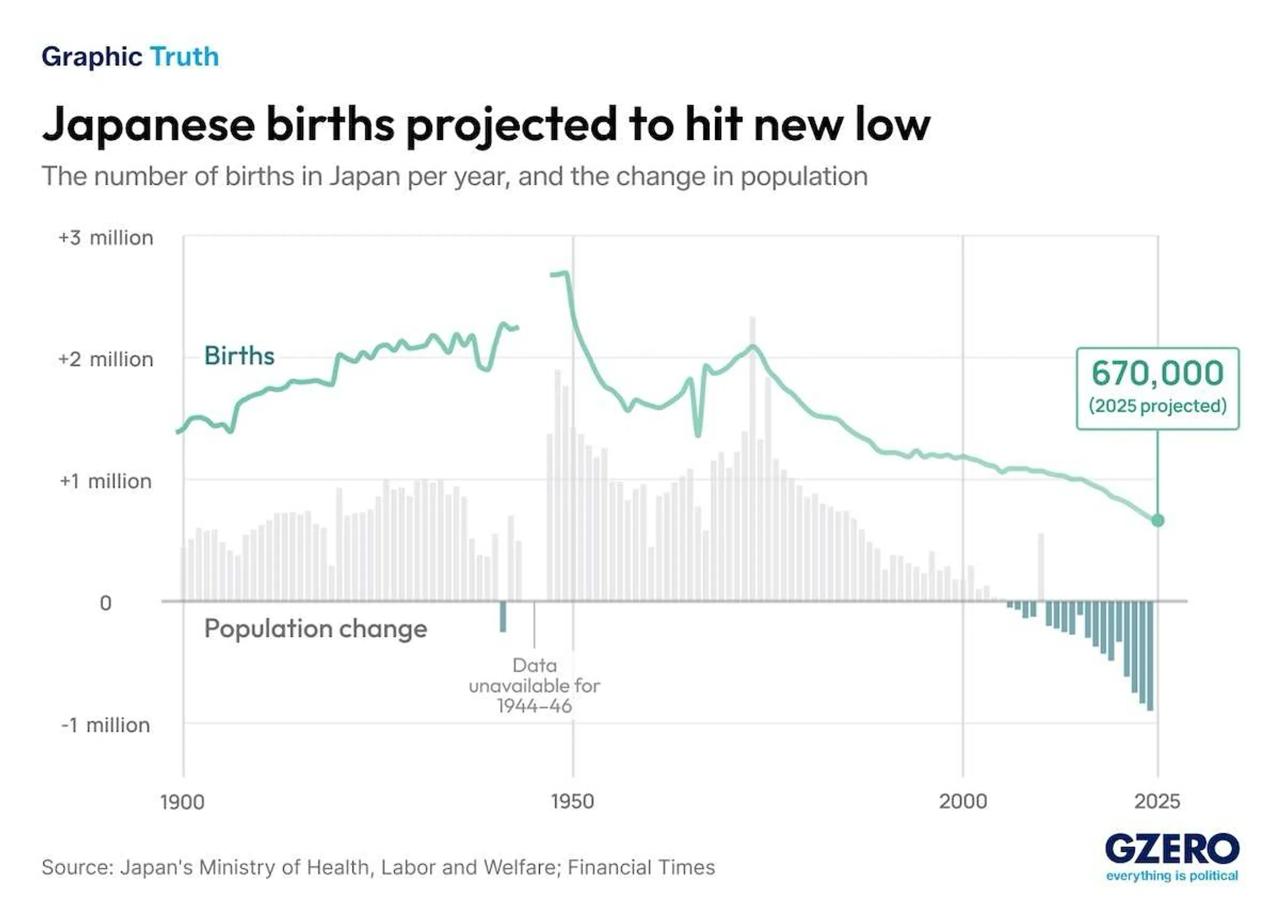

Japan's fertility crisis has reached a new and alarming milestone. Preliminary data and projections indicate that the number of births in 2025 will fall below 670,000 — the lowest annual figure since national statistics began in 1899.

This marks the tenth consecutive year of record-low births and comes in significantly below even the most pessimistic government forecasts.

This marks the tenth consecutive year of record-low births and comes in significantly below even the most pessimistic government forecasts.

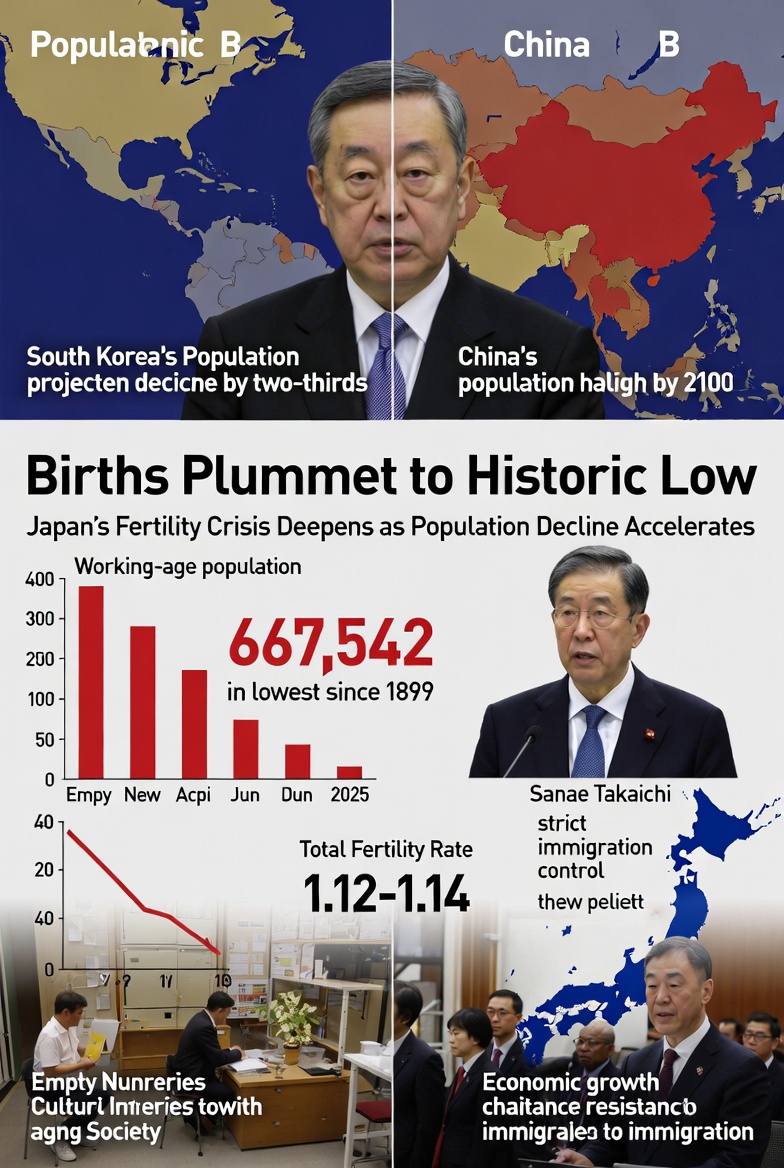

The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research had projected 749,000 births for 2025 in its 2023 medium-variant scenario, with no expectation of a drop below 670,000 until 2041. Instead, demographers now estimate around 667,542 births for the year, a sharp acceleration of the long-term decline.

The first half of 2025 already showed a troubling trend: only 339,280 babies were born from January to June, down 3.1% (or about 10,794 fewer births) from the same period in 2024. If the second half follows a similar trajectory, 2025 will confirm a full-year record low. This follows 2024's 686,061 births (excluding foreign nationals in some counts), which itself was the first year below 700,000 in modern records.

Japan's total fertility rate (TFR) — the average number of children a woman would have over her lifetime — remains critically low. Recent estimates place it around 1.12–1.14 in 2025, far below the 2.1 replacement level needed for population stability without immigration. The crude birth rate has hovered around 5.5–5.8 per 1,000 people in recent years, reflecting fewer women of childbearing age and persistent social and economic barriers to family formation.

Japan's total fertility rate (TFR) — the average number of children a woman would have over her lifetime — remains critically low. Recent estimates place it around 1.12–1.14 in 2025, far below the 2.1 replacement level needed for population stability without immigration. The crude birth rate has hovered around 5.5–5.8 per 1,000 people in recent years, reflecting fewer women of childbearing age and persistent social and economic barriers to family formation.

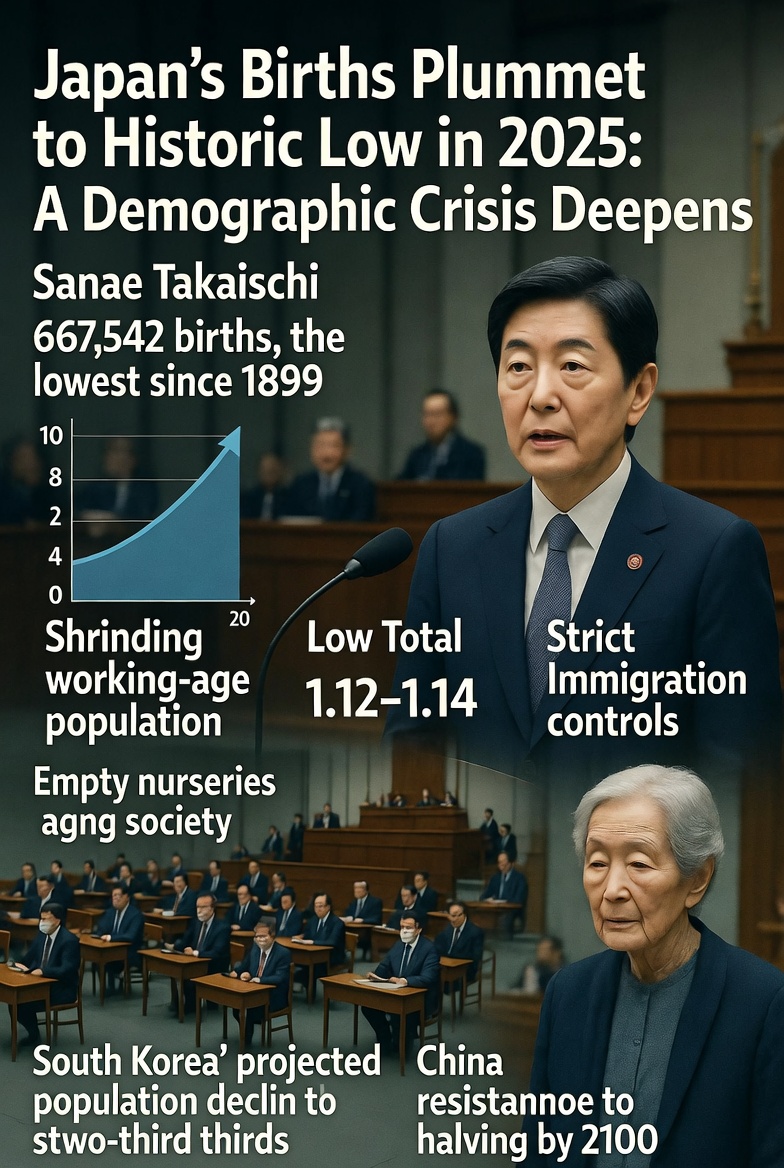

This demographic collapse poses an existential challenge for Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, who assumed office in late 2025. In her first policy speech to the Diet, Takaichi described Japan's shrinking population as the country's "greatest problem." She has prioritized child-rearing support, tax reforms to reduce disincentives for second earners, and discussions on social security sustainability.

A new high-level body, potentially called the "Population Strategy Headquarters," is expected to coordinate efforts to reverse the decline. However, Takaichi faces the difficult task of balancing economic growth with strict immigration controls — a stance rooted in cultural and political preferences for homogeneity.

Japan's reluctance to embrace large-scale immigration exacerbates the crisis. While foreign births have risen slightly (reaching a record in 2024), the overall population continues to shrink rapidly. The working-age population is projected to fall significantly by 2050, threatening labor supply, tax revenues, and social security funding.

The trend is stark across East Asia. In South Korea, the world's lowest fertility rate (0.721 in 2023, with a slight uptick to 0.748 in 2024) has triggered fears of dramatic decline. Projections suggest the population could shrink by more than two-thirds over the next century — potentially dropping from 51.7 million today to as low as 7.5–15 million by 2125 under worst-case scenarios — if current patterns persist.

The trend is stark across East Asia. In South Korea, the world's lowest fertility rate (0.721 in 2023, with a slight uptick to 0.748 in 2024) has triggered fears of dramatic decline. Projections suggest the population could shrink by more than two-thirds over the next century — potentially dropping from 51.7 million today to as low as 7.5–15 million by 2125 under worst-case scenarios — if current patterns persist.

China faces a similar trajectory. After peaking at 1.4 billion, its population began shrinking in 2022. United Nations estimates project it could fall to around 770 million by 2100, or even 525–633 million in some analyses — roughly half its current size. The rapid aging and shrinking workforce threaten economic dynamism and social stability.

Japan's experience serves as a warning for aging societies worldwide. Despite generous child allowances, expanded parental leave, and campaigns to encourage marriage and childbearing, structural factors — high living costs, long working hours, gender imbalances in domestic labor, and shifting cultural attitudes — continue to suppress births. Without bolder reforms or a shift in immigration policy, the demographic contraction will accelerate, straining pensions, healthcare, and economic vitality.

As Prime Minister Takaichi confronts this "national emergency," the question is whether targeted interventions can reverse decades of decline — or if Japan, and much of East Asia, is entering an era of irreversible shrinkage. The stakes are immense: a future where fewer young people support a growing elderly population risks economic stagnation and social strain on an unprecedented scale.

Also read:

- AI Takes Center Stage in Learning: Insights from the Latest Google-Ipsos Study and Beyond

- China's 'Are You Dead?' App Tops Charts, Sparking Debate on Urban Isolation

- Crowded Skies: Starlink's Orbital Shift to Ease Satellite Congestion

Thank you!