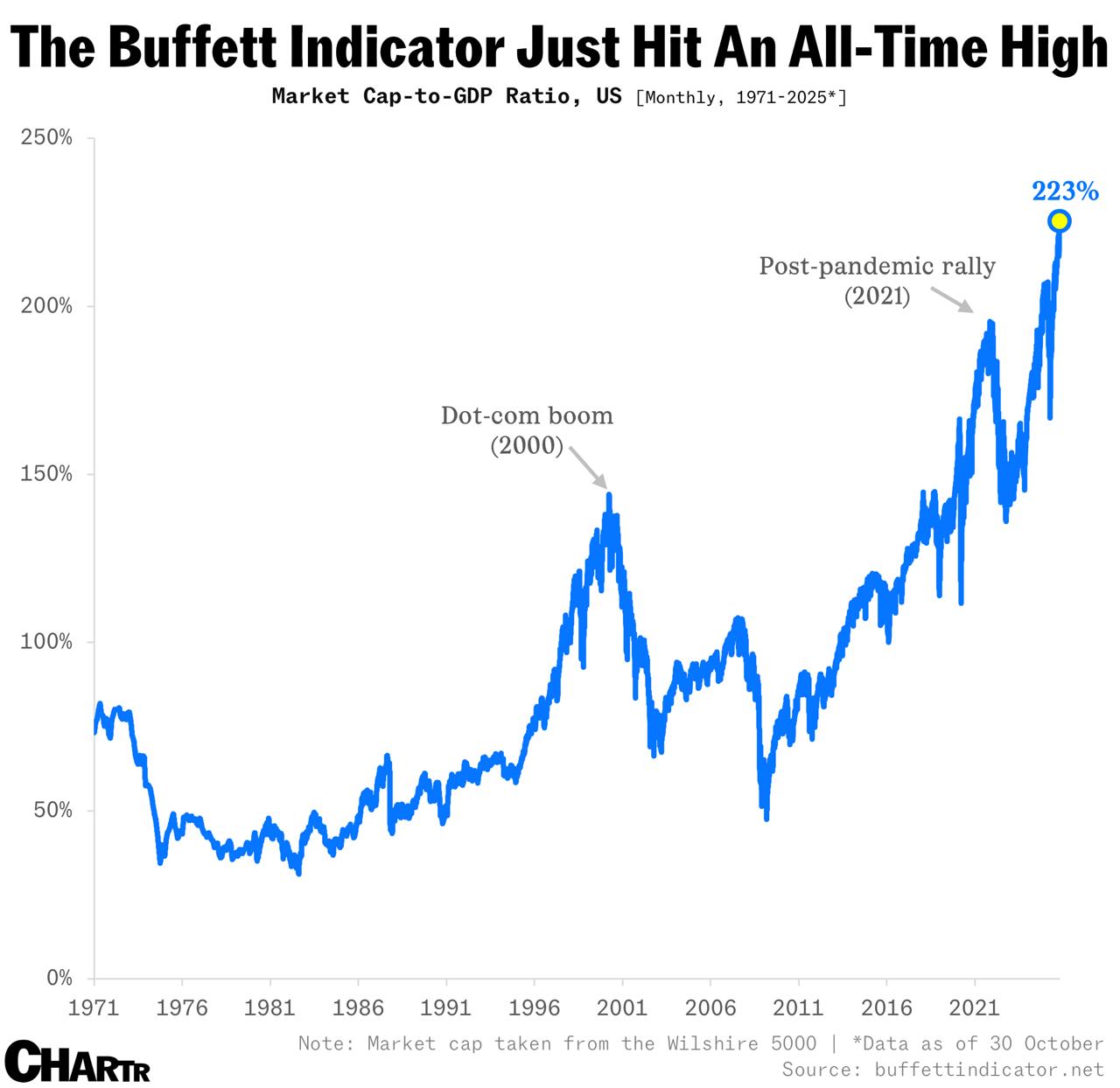

Warren Buffett once popularized a simple yet provocative metric to gauge stock market valuations: the ratio of the total U.S. stock market capitalization to the country's gross domestic product (GDP). Known as the Buffett Indicator, it has surged to an all-time high of 225%. Buffett himself warned that levels approaching 200% should raise alarms, signaling potential overvaluation. With investors paying record premiums for future S&P 500 revenues and nearly 40% of the index's value concentrated in just eight tech giants, the question looms: Is the market dangerously overheated, or are there mitigating factors at play?

The Flawed but Famous Comparison

At its core, comparing market capitalization to GDP is inherently imperfect. GDP measures the annual flow of goods and services produced within a country - an economic output over a year. Market cap, by contrast, is a snapshot of the total value of publicly traded companies' equity at a single point in time. It's like equating a company's lifetime asset worth to its yearly sales; the metrics operate on different timescales and logics.

At its core, comparing market capitalization to GDP is inherently imperfect. GDP measures the annual flow of goods and services produced within a country - an economic output over a year. Market cap, by contrast, is a snapshot of the total value of publicly traded companies' equity at a single point in time. It's like equating a company's lifetime asset worth to its yearly sales; the metrics operate on different timescales and logics.

Despite this conceptual mismatch, Buffett elevated the indicator in a 2001 Fortune article, calling it "probably the best single measure of where valuations stand at any given moment."

He noted that ratios around 70-80% historically signaled undervaluation, while anything near or above 100% suggested caution. The metric gained traction for its simplicity, especially during bubbles like the dot-com era, when it spiked before the 2000 crash.

Today, at 225%, it dwarfs even the peaks of past manias. The Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index (a broad proxy for U.S. market cap) now stands at roughly $55 trillion, compared to U.S. GDP of about $24.5 trillion (based on recent estimates). This isn't just elevated - it's unprecedented.

Signs of Froth: Premiums and Concentration

The euphoria is evident in forward-looking metrics. Investors are paying a record multiple for the S&P 500's anticipated revenues, with the price-to-sales ratio hovering at levels not seen since the early 2000s tech bubble.

The euphoria is evident in forward-looking metrics. Investors are paying a record multiple for the S&P 500's anticipated revenues, with the price-to-sales ratio hovering at levels not seen since the early 2000s tech bubble.

This reflects optimism about earnings growth, but it also means the market is pricing in flawless execution amid uncertainties.

Compounding the concern is concentration risk. Approximately 40% of the S&P 500's market cap is tied to eight mega-cap technology firms - often dubbed the "Magnificent Eight" (including Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, Amazon, Meta, Alphabet, Tesla, and Broadcom).

These companies dominate narratives around AI, cloud computing, and digital transformation, driving disproportionate gains.

While innovation justifies premiums, such heavy reliance on a handful of stocks echoes the Nifty Fifty era of the 1970s, where overconcentration preceded sharp corrections.

Buffett's threshold of 200% as a "play with fire" zone seems breached. If history is any guide, elevated readings have preceded downturns, though timing remains elusive.

Counterarguments: Why Panic Might Be Premature

Yet, the bull case is robust, challenging the indicator's alarmist signal. First, globalization distorts the GDP comparison. Nearly half of the revenue for the "Magnificent Seven" (a subset of the eight) comes from overseas markets. U.S. GDP captures only domestic production, ignoring the global earnings power of American multinationals. Adjusting for this - perhaps by comparing market cap to global GDP or worldwide corporate profits - paints a less extreme picture. The U.S. market isn't just a proxy for the American economy; it's a bet on worldwide growth.

Yet, the bull case is robust, challenging the indicator's alarmist signal. First, globalization distorts the GDP comparison. Nearly half of the revenue for the "Magnificent Seven" (a subset of the eight) comes from overseas markets. U.S. GDP captures only domestic production, ignoring the global earnings power of American multinationals. Adjusting for this - perhaps by comparing market cap to global GDP or worldwide corporate profits - paints a less extreme picture. The U.S. market isn't just a proxy for the American economy; it's a bet on worldwide growth.

Profitability bolsters the optimism. S&P 500 operating margins now exceed 14%, a historical record fueled by tech efficiencies, pricing power, and cost discipline. High margins suggest companies can sustain earnings even if growth slows, providing a buffer against valuation compression.

Valuation metrics beyond the Buffett Indicator appear reasonable when growth is factored in. The price-to-earnings-growth (PEG) ratio for the S&P 500 hovers around 1.5-2.0, within norms for a low-interest-rate environment with accelerating profits. Forward P/E ratios, while elevated at ~22x, are supported by expected EPS growth of 12-15% annually, driven by AI investments.

Valuation metrics beyond the Buffett Indicator appear reasonable when growth is factored in. The price-to-earnings-growth (PEG) ratio for the S&P 500 hovers around 1.5-2.0, within norms for a low-interest-rate environment with accelerating profits. Forward P/E ratios, while elevated at ~22x, are supported by expected EPS growth of 12-15% annually, driven by AI investments.

Macro tailwinds amplify this. The Federal Reserve's signaled rate cuts, stable inflation around 2-3%, and burgeoning AI adoption create a fertile backdrop. Lower borrowing costs reduce discount rates for future cash flows, justifying higher multiples. Hopes for AI aren't mere hype; capital expenditures by tech giants are translating into productivity gains, with early evidence from cloud and chip sectors.

Also read:

- The Silver Market's Dramatic Shift: From Surplus to Chronic Deficit

- Global Billionaire Boom: 3,279 Tycoons Control $15 Trillion

- When Civilization Stumbles: $20 Billion for the Birds

A Record in Context

The Buffett Indicator's 225% pinnacle emerges from this confluence: concentrated tech leadership, global revenue streams, peak margins, growth-adjusted valuations, and supportive policy. It's not the 1999 bubble redux, where margins were thin and international exposure limited. Instead, it reflects a structurally profitable, globally oriented market.

The Buffett Indicator's 225% pinnacle emerges from this confluence: concentrated tech leadership, global revenue streams, peak margins, growth-adjusted valuations, and supportive policy. It's not the 1999 bubble redux, where margins were thin and international exposure limited. Instead, it reflects a structurally profitable, globally oriented market.

That said, risks persist - geopolitical tensions, regulatory scrutiny on Big Tech, or a growth disappointment could trigger repricing. Buffett's metric, flaws notwithstanding, serves as a reminder: Trees don't grow to the sky. Investors should weigh concentration, monitor margins for sustainability, and diversify beyond U.S. mega-caps.

In the end, the market may be expensive, but not necessarily irrational. At 225%, it's flashing yellow, not red - urging vigilance rather than exodus. As Buffett might say, be fearful when others are greedy, but greedy only when the fundamentals align. For now, they largely do.

Author: Slava Vasipenok

Founder and CEO of QUASA (quasa.io) - Daily insights on Web3, AI, Crypto, and Freelance. Stay updated on finance, technology trends, and creator tools - with sources and real value.

Innovative entrepreneur with over 20 years of experience in IT, fintech, and blockchain. Specializes in decentralized solutions for freelancing, helping to overcome the barriers of traditional finance, especially in developing regions.

This is not financial or investment advice. Always do your own research (DYOR).