Competition between companies is a cornerstone of economic growth. It drives down prices, enhances product quality, and spurs innovation. Nearly everyone acknowledges its benefits, which is why governments safeguard it through laws and regulatory bodies. However, the toughest challenge is determining whether true competition exists. Authorities often rely on simplistic yet flawed indicators, ultimately hindering progress by blocking mergers and reforms that could yield significant advantages.

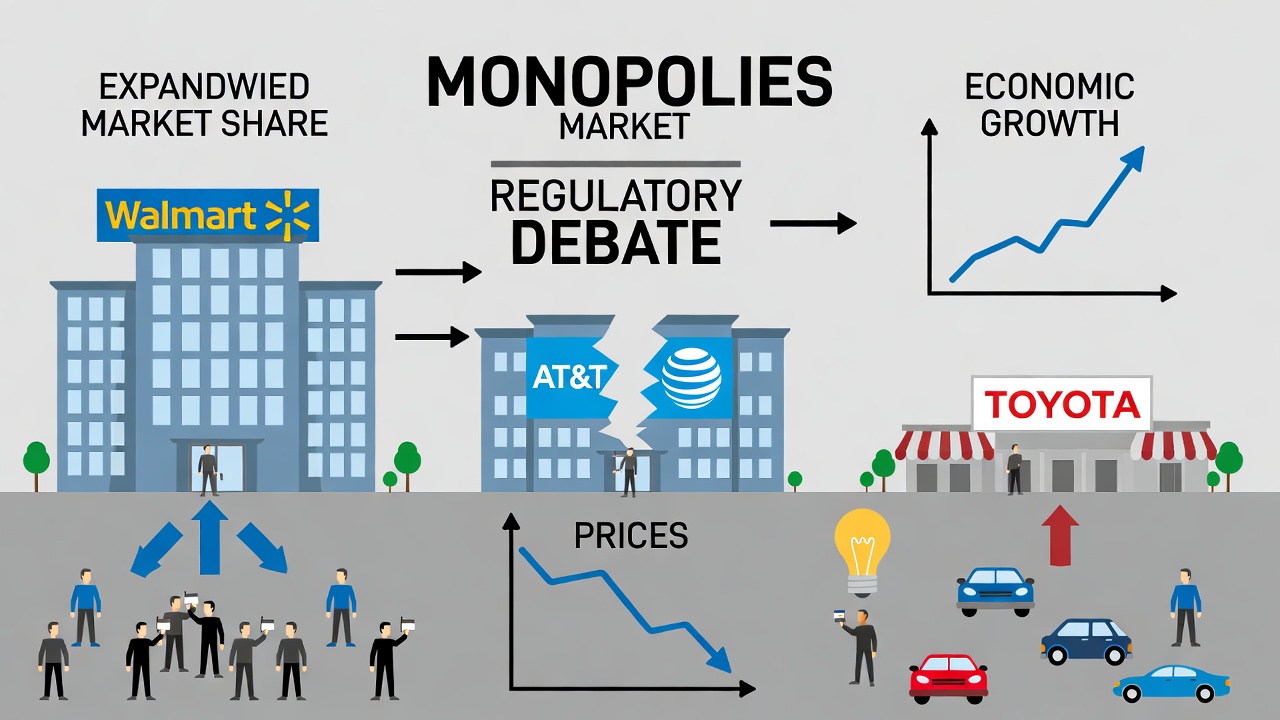

A common misconception is that markets dominated by a few large firms are inherently bad, while those with numerous small players are good. Yet data tells a different story. In the U.S., from 1992 to 2012, the national market share of large retail chains tripled.

A common misconception is that markets dominated by a few large firms are inherently bad, while those with numerous small players are good. Yet data tells a different story. In the U.S., from 1992 to 2012, the national market share of large retail chains tripled.

This might suggest diminishing competition. But at the local level — in cities and neighborhoods — the number of competing stores rose by about a third. The reason? Chains like Walmart expanded into areas previously served by just a handful of local shops. As a result, consumers gained broader choices and lower prices, thanks to economies of scale in purchasing and technological investments.

Another misguided benchmark is high profits or markups. If a company sells products far above cost, it's easy to label it abusive. But elevated profits often reward risk-taking and years of development.

Take Novo Nordisk, the maker of popular weight-loss drugs: its operating profits grew by 27.6% in 2022, 37.1% in 2023, and 25.1% in 2024. Capping such earnings would erode incentives for innovation.

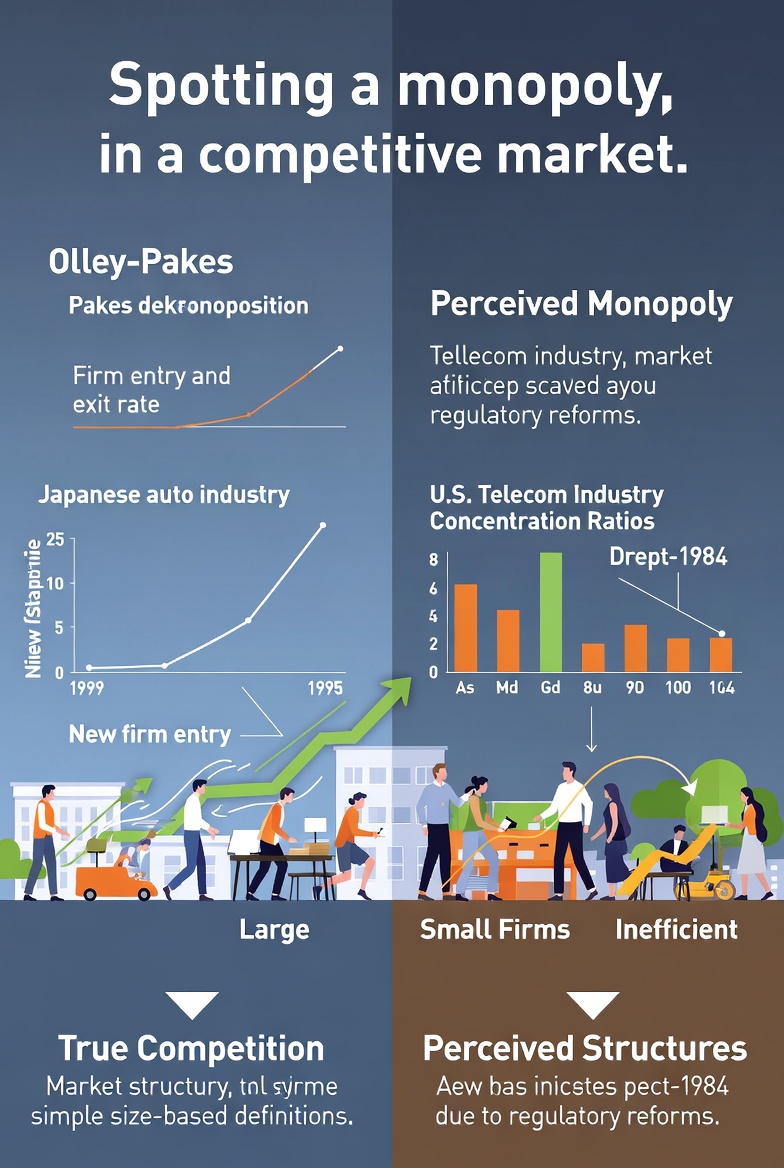

A more reliable gauge of competition is how customers and revenue flow. In economics, this is captured by the Olley-Pakes decomposition. The idea is straightforward: In a healthy market, efficient firms expand and capture larger shares, while inefficient ones contract or exit. Overall productivity growth then stems not just from internal improvements but from resources reallocating toward top performers.

This dynamic played out in Japan's auto industry. In 1950, the entire sector produced about 31,000 vehicles annually — equivalent to one day of U.S. output. Japanese firms were resource-strapped but rapidly boosted efficiency. At Toyota, a worker handled one machine in 1946, three by 1949, and five by 1963. Over time, buyers recognized the superior reliability and affordability of Japanese cars, shifting demand to these efficient producers.

This dynamic played out in Japan's auto industry. In 1950, the entire sector produced about 31,000 vehicles annually — equivalent to one day of U.S. output. Japanese firms were resource-strapped but rapidly boosted efficiency. At Toyota, a worker handled one machine in 1946, three by 1949, and five by 1963. Over time, buyers recognized the superior reliability and affordability of Japanese cars, shifting demand to these efficient producers.

A similar shift occurred in the U.S. after dismantling AT&T's monopoly. Before reforms, the company controlled about 75% of local networks and nearly all equipment. Post-1968, the number of manufacturers surged from 164 to 584 by 1987. Competition intensified: 60% of firms operating in 1972 vanished within 15 years. The correlation between efficiency and market share climbed from 0.01 to 0.35 by 1981 — superior players began dominating.

In Colombia during the early 1990s, slashing trade barriers transformed the landscape. Pre-reform, average tariffs stood at 62%, soaring to 200% on imported cars, inflating prices two to three times above global levels. After dropping to 15%, available models jumped from 26 in 1991 to 71 in 1992. Car prices fell from $25,000 in 1987 to $15,000 in 1997, sales doubled, and overall productivity rose 8% through reallocation to superior factories.

Contrast this with Britain post-2008 crisis, where the system faltered. Inefficient "zombie" firms lingered: company mortality was half the expected rate. Consequently, from 2010 to 2019, productivity grew just 5.8%, versus 8% in the U.S. and 9.6% in France. The market failed to reward excellence.

The lesson is clear: Don't gauge competition solely by firm count or profit levels. Focus on whether resources migrate to the most effective operators. That's the true litmus test for a vibrant economy.

Also read:

Also read:

- Instagram's Wake-Up Call: Adam Mosseri on Navigating the AI Flood in 2026

- The AI Hallucination Epidemic: How Fabricated Facts Are Overburdening Libraries and Eroding Trust in Knowledge

- France Enters Era of Natural Population Decline: A Historic Shift

- Reflecting on Robert Solow's Profound Insights: A 98-Year-Old Nobel Laureate's Final Interview

Thank you!