In a groundbreaking stride toward mimicking the human brain’s remarkable capabilities, researchers from Stanford University, Sandia National Laboratories, and Purdue University have developed artificial neurons that can simultaneously process and transmit both electrical and optical signals, closely resembling the functionality of biological brain cells. This innovation marks a significant step forward in neuromorphic computing, with the potential to revolutionize how we design brain-inspired systems.

Emulating the Brain’s Dual Signaling

The human brain is a marvel of efficiency, relying on short electrical impulses to facilitate communication between neurons for local processing. However, for long-distance signaling, biological systems often leverage optical-like mechanisms, such as those observed in certain neural pathways or bioluminescent processes.

The human brain is a marvel of efficiency, relying on short electrical impulses to facilitate communication between neurons for local processing. However, for long-distance signaling, biological systems often leverage optical-like mechanisms, such as those observed in certain neural pathways or bioluminescent processes.

Traditional neuromorphic chips, which aim to replicate the brain’s computational architecture, have primarily focused on mimicking these electrical impulses. While effective for local computations, these systems struggle with long-range communication, as electrical signals degrade over distance and require energy-intensive conversions to interface with optical systems.

The new electro-optical Mott neurons, crafted from niobium dioxide (NbO₂), address this critical gap. These artificial neurons generate synchronized electrical and optical pulses, enabling both local computation and long-distance communication within a single device. Each electrical spike, which mirrors the brain’s neural firing, is accompanied by a visible light emission peaking at around 810 nm, allowing for seamless integration of computation and communication.

The Power of Niobium Dioxide

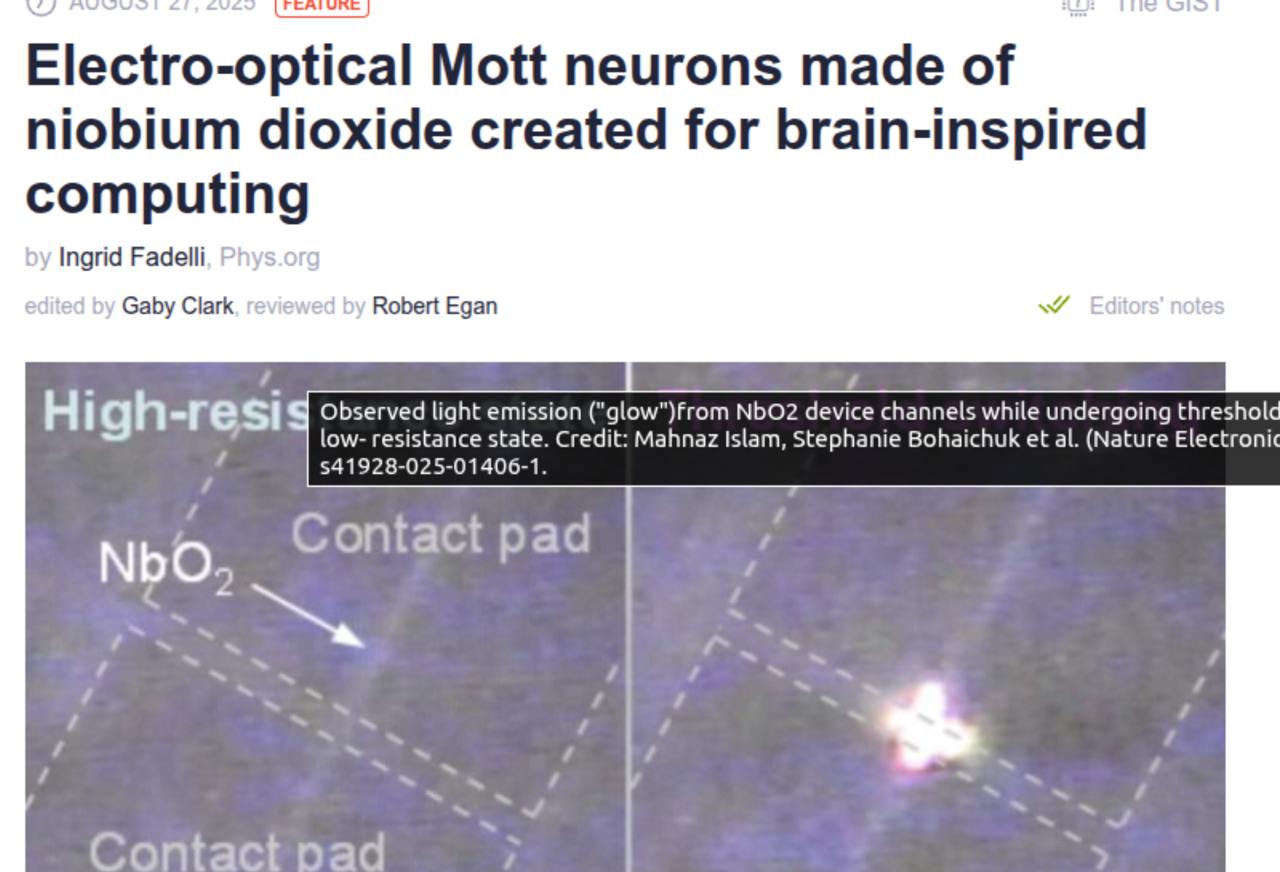

The breakthrough hinges on the unique properties of niobium dioxide, a Mott insulator-metal transition material. Researchers, initially studying electrical switching in NbO₂ devices, unexpectedly discovered a bright visible glow during high-field transport, which they traced to charge carrier relaxation—an electronic phenomenon that produces light without requiring external sources. By fabricating micrometer-scale devices with thin NbO₂ films and metal contacts, the team created artificial neurons capable of neuron-like oscillations and synchronized electro-optical signaling.

The breakthrough hinges on the unique properties of niobium dioxide, a Mott insulator-metal transition material. Researchers, initially studying electrical switching in NbO₂ devices, unexpectedly discovered a bright visible glow during high-field transport, which they traced to charge carrier relaxation—an electronic phenomenon that produces light without requiring external sources. By fabricating micrometer-scale devices with thin NbO₂ films and metal contacts, the team created artificial neurons capable of neuron-like oscillations and synchronized electro-optical signaling.

As Eric Pop, co-senior author of the study, explained, “This work began as a simple study of switching in niobium dioxide devices. While monitoring them for signs of electrical breakdown, we noticed an unexpected, bright visible glow from the NbO₂ channel.” This serendipitous discovery opened the door to a new class of neuromorphic devices that combine the best of both worlds: electrical precision for computation and optical efficiency for communication.

A Paradigm Shift for Neuromorphic Computing

Most existing neuron-inspired devices rely solely on electrons or photons, but integrating the two has been challenging due to the stark differences in their architectures. Converting signals between electronic and photonic systems often leads to energy losses and requires costly equipment. The electro-optical Mott neurons eliminate the need for such conversions by embedding both functions within a single material. This dual-domain capability allows for faster, more energy-efficient processing and signaling, paving the way for scalable neuromorphic systems.

Most existing neuron-inspired devices rely solely on electrons or photons, but integrating the two has been challenging due to the stark differences in their architectures. Converting signals between electronic and photonic systems often leads to energy losses and requires costly equipment. The electro-optical Mott neurons eliminate the need for such conversions by embedding both functions within a single material. This dual-domain capability allows for faster, more energy-efficient processing and signaling, paving the way for scalable neuromorphic systems.

Mahnaz Islam, the study’s first author, highlighted the potential for future advancements: “In future work, we plan to scale and integrate NbO₂ electro-optical neurons into larger arrays where devices can communicate optically with each other, enabling the study of light-mediated signaling in neuromorphic networks.” The team aims to enhance the devices’ light-capturing and guiding efficiency through optical engineering techniques, such as on-chip waveguides, and to improve the quality of NbO₂ samples to boost conversion efficiency.

Implications for Brain-Inspired Technology

This development has far-reaching implications for brain-inspired computing and beyond. By enabling artificial neurons to perform both computation and communication without separate transducers, these devices could lead to more compact, energy-efficient systems for applications ranging from artificial intelligence to on-chip vision systems. The ability to integrate electrical and optical functions in a single chip could reduce reliance on bulky, power-hungry components, making neuromorphic systems more practical for real-world use.

This development has far-reaching implications for brain-inspired computing and beyond. By enabling artificial neurons to perform both computation and communication without separate transducers, these devices could lead to more compact, energy-efficient systems for applications ranging from artificial intelligence to on-chip vision systems. The ability to integrate electrical and optical functions in a single chip could reduce reliance on bulky, power-hungry components, making neuromorphic systems more practical for real-world use.

Moreover, this work aligns with broader efforts in neuromorphic computing, such as explorations of systems with billions of artificial neurons. While some projects focus on scaling neuromorphic architectures, the electro-optical neurons offer a complementary approach by enhancing the functionality of individual neurons. Together, these advancements signal a future where brain-like systems could achieve unprecedented efficiency and adaptability.

Also read:

- Ukrainian Parliament Approves Crypto Legalization Bill in First Reading

- BitMine Bolsters Ethereum Reserve to $8.15 Billion

- Xiaomi Unveils a Giant Wheeled Tablet: A 27-Inch Full HD Touchscreen That Redefines Mobile Entertainment

Looking Ahead

The creation of electro-optical Mott neurons represents a pivotal moment in the quest for brain-on-a-chip technologies. By bridging the gap between electrical and optical signaling, these devices bring us closer to replicating the brain’s remarkable ability to process and communicate information efficiently. As researchers continue to refine these neurons and integrate them into larger arrays, the potential for breakthroughs in AI, neural interfaces, and beyond grows ever more tangible.

This innovation not only showcases the power of interdisciplinary collaboration but also underscores the importance of exploring unconventional materials like niobium dioxide. As the field of neuromorphic computing evolves, these electro-optical neurons could light the way — quite literally — toward a new era of brain-inspired technology.