The U.S. official poverty line — a benchmark used to measure economic hardship and determine eligibility for programs like SNAP, Medicaid, and tax credits — remains rooted in a formula from the 1960s. Developed by economist Mollie Orshansky, it estimates the minimum cost of a basic food budget (based on 1963 USDA plans) and multiplies it by three, assuming food accounted for roughly one-third of household spending at the time.

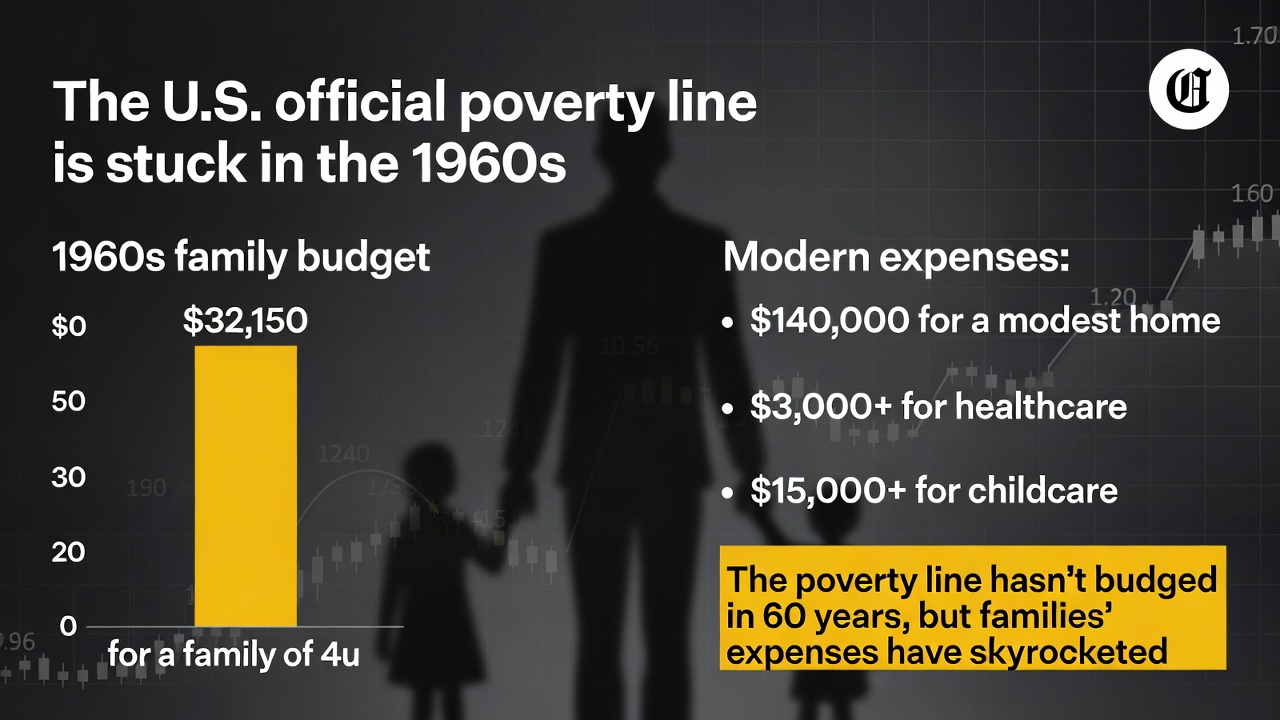

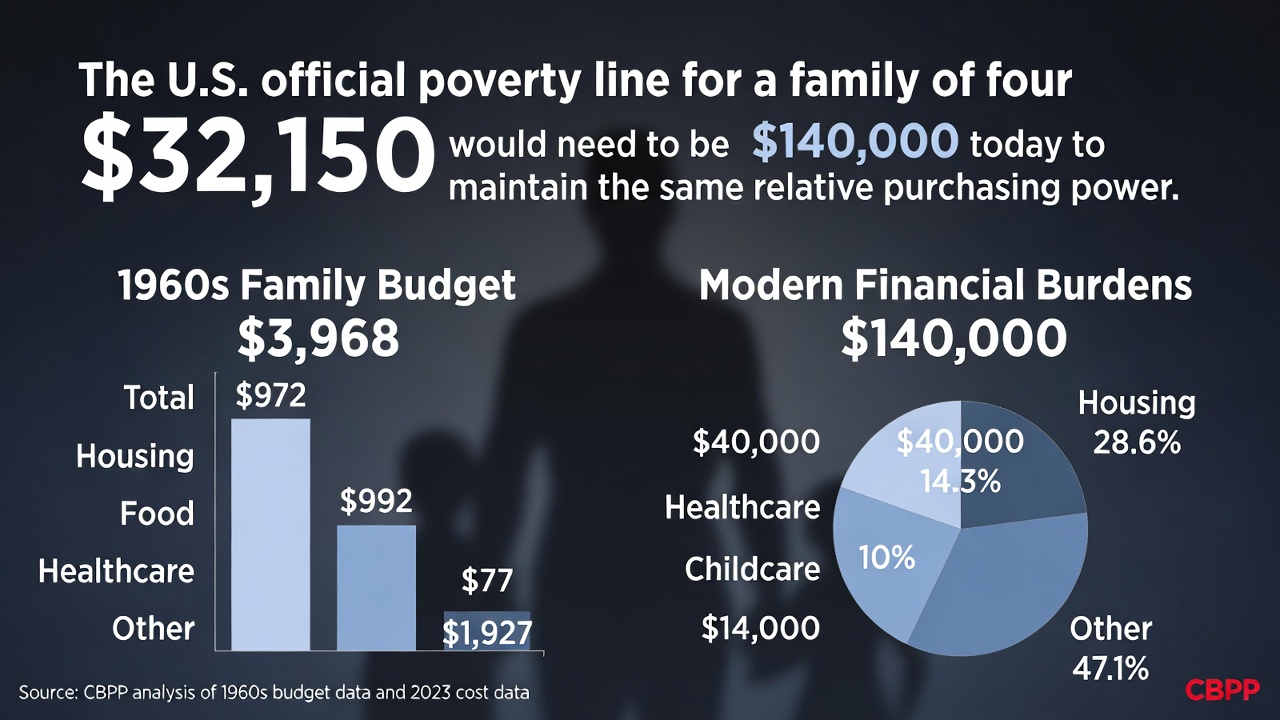

For a family of four in the contiguous United States, the 2025–2026 federal poverty guideline stands at approximately $32,150 annually (with slight annual adjustments for inflation). This figure is what officially defines poverty for statistical and administrative purposes.

Yet this measure is widely criticized as outdated. Modern household budgets bear little resemblance to those of the 1960s. Housing, healthcare, childcare, transportation, and other essentials now consume far more than two-thirds of income for most families.

Yet this measure is widely criticized as outdated. Modern household budgets bear little resemblance to those of the 1960s. Housing, healthcare, childcare, transportation, and other essentials now consume far more than two-thirds of income for most families.

Food, meanwhile, has shrunk to a much smaller share of spending (often 7–10% for middle-income households). The original multiplier of three no longer captures reality.

The True Cost of Economic Stability

Alternative calculations that attempt to reflect current living costs paint a starkly different picture.

Recent analyses — including prominent discussions by strategists and economists in late 2025 — have reconstructed a "critical minimum" or "basic family budget" for a family of four, incorporating realistic expenses:

Recent analyses — including prominent discussions by strategists and economists in late 2025 — have reconstructed a "critical minimum" or "basic family budget" for a family of four, incorporating realistic expenses:

- Housing (modest rent or mortgage in average markets);

- Healthcare (premiums, out-of-pocket costs);

- Childcare (for two young children);

- Transportation (car ownership, gas, maintenance);

- Food (beyond bare minimum);

- Utilities, taxes, and other necessities.

These estimates frequently land in the range of $130,000–$150,000 gross annual income — often cited around $140,000 as a conservative national average. This figure aligns with data from sources like the MIT Living Wage Calculator (adjusted for national averages) and detailed breakdowns of contemporary household spending patterns.

At $140,000, a family can cover essentials without constant reliance on debt, government assistance, or extreme trade-offs — leaving room for modest savings or unexpected shocks. Below that threshold, many households face chronic financial strain, even if they exceed the official poverty line.

The Real Problem: Systemic Undermeasurement

The core issue is not poor math — it's a deliberate or inertial choice to retain a metric that systematically understates economic vulnerability. By pegging poverty at roughly one-third of what a realistic minimum requires, the official line renders millions of struggling households statistically "not poor."

The core issue is not poor math — it's a deliberate or inertial choice to retain a metric that systematically understates economic vulnerability. By pegging poverty at roughly one-third of what a realistic minimum requires, the official line renders millions of struggling households statistically "not poor."

- A family earning $60,000–$80,000 (well above the poverty line) may still live paycheck-to-paycheck, with no buffer for emergencies.

- Households at $100,000 can appear middle-class on paper but face eviction risks, medical debt, or inability to save for retirement or college.

- The result: widespread economic insecurity — defined as inability to absorb a modest financial shock without hardship — affects far more Americans than the official poverty rate (~11–12%) suggests.

Studies consistently show that 40–50%+ of U.S. households live with some degree of economic fragility, even when above the poverty threshold. Food insecurity, housing instability, and medical debt persist in families officially classified as "middle income."

Also read:

- NEET Is Failing Us: How Flat Statistics Mask the Rise of Disconnected Young Men

- Apple's Big Gift to iOS Developers: Agentic Coding Arrives in Xcode 26.3

- Tesla's Bold Pivot: Fremont Factory Shifts from Model S/X to Mass-Producing Optimus Humanoid Robots

- Riverflow 2.0: Sourceful's New Powerhouse for Photorealistic AI Image Generation and Editing

Why It Matters — and Why It Persists

This disconnect has profound consequences:

- It masks the true scale of hardship, reducing political urgency for policies addressing housing affordability, childcare costs, healthcare reform, and wage stagnation.

- It distorts eligibility for safety-net programs, leaving many vulnerable families without support.

- It perpetuates a narrative that poverty is a marginal issue rather than a structural one affecting broad swaths of the working and lower-middle class.

Critics argue the poverty line should be updated — perhaps by adopting a modern "basic family budget" approach or using a Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), which already incorporates additional costs and benefits but remains secondary to the official rate.

Until then, the official threshold continues to hide in plain sight the precarious reality of millions: families who are formally "above poverty" but live one illness, job loss, or rent increase away from crisis. The problem is not that people are miscounting poverty — it's that the metric itself systematically erases it.