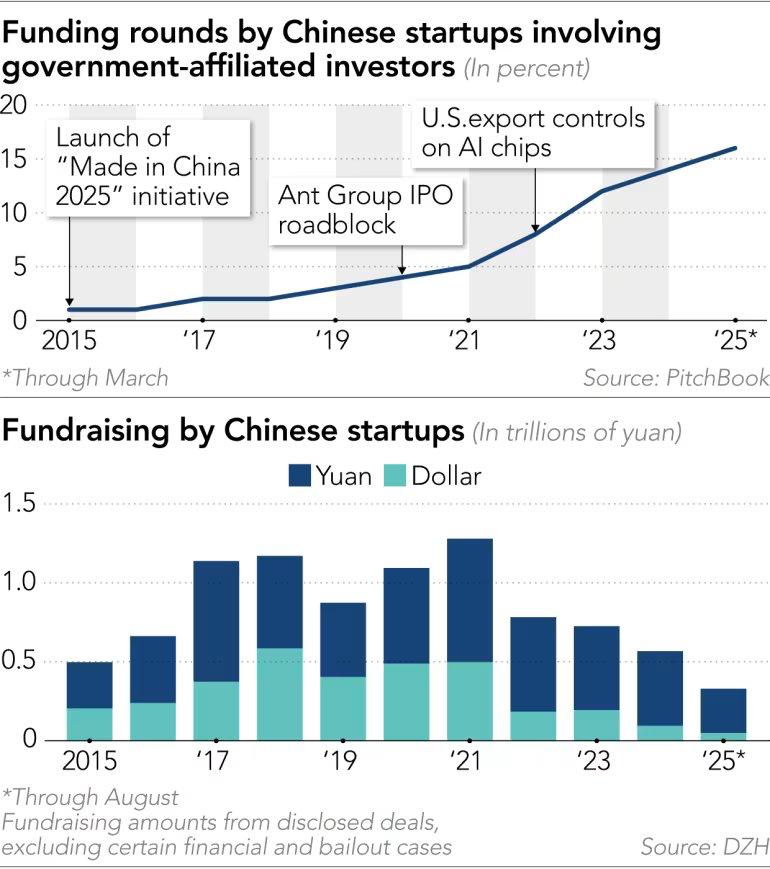

In the first eight months of 2025, Chinese technology startups raised only $6.6 billion from foreign investors — a mere 10 % of total fundraising, down from roughly 50 % in 2018 and 30 % as recently as 2021, according to PitchBook and China’s Zero2IPO Research.

The shift is dramatic and deliberate.

The shift is dramatic and deliberate.

Beijing’s tightening of cross-border capital controls, combined with escalating U.S. export restrictions and investment screening, has pushed China’s entrepreneurial ecosystem into a new, more self-reliant era dominated by domestic — and increasingly state-linked — funding.

The numbers tell the story clearly.

- Total disclosed fundraising by Chinese startups through August 2025 reached approximately 460 billion yuan ($64 billion), of which dollar-denominated rounds accounted for just over $6.6 billion (DZH Research / PitchBook).

- Government-affiliated investors (state guidance funds, local government platforms, and sovereign funds) participated in 16 % of early-stage rounds in 2024–2025, up from under 5 % a decade earlier (PitchBook, March 2025).

- The share of funding rounds involving at least one government-linked entity jumped from ~8 % in 2019 to over 18 % by mid-2025 (PitchBook).

This pivot is not merely financial; it is strategic. As U.S. policy has moved from targeted export controls to broad investment restrictions — including the August 2024 Executive Order on outbound investment in semiconductors, quantum computing, and AI, and the January 2025 implementation rules — Chinese founders have rapidly reoriented toward yuan-denominated capital that carries fewer geopolitical strings.

This pivot is not merely financial; it is strategic. As U.S. policy has moved from targeted export controls to broad investment restrictions — including the August 2024 Executive Order on outbound investment in semiconductors, quantum computing, and AI, and the January 2025 implementation rules — Chinese founders have rapidly reoriented toward yuan-denominated capital that carries fewer geopolitical strings.

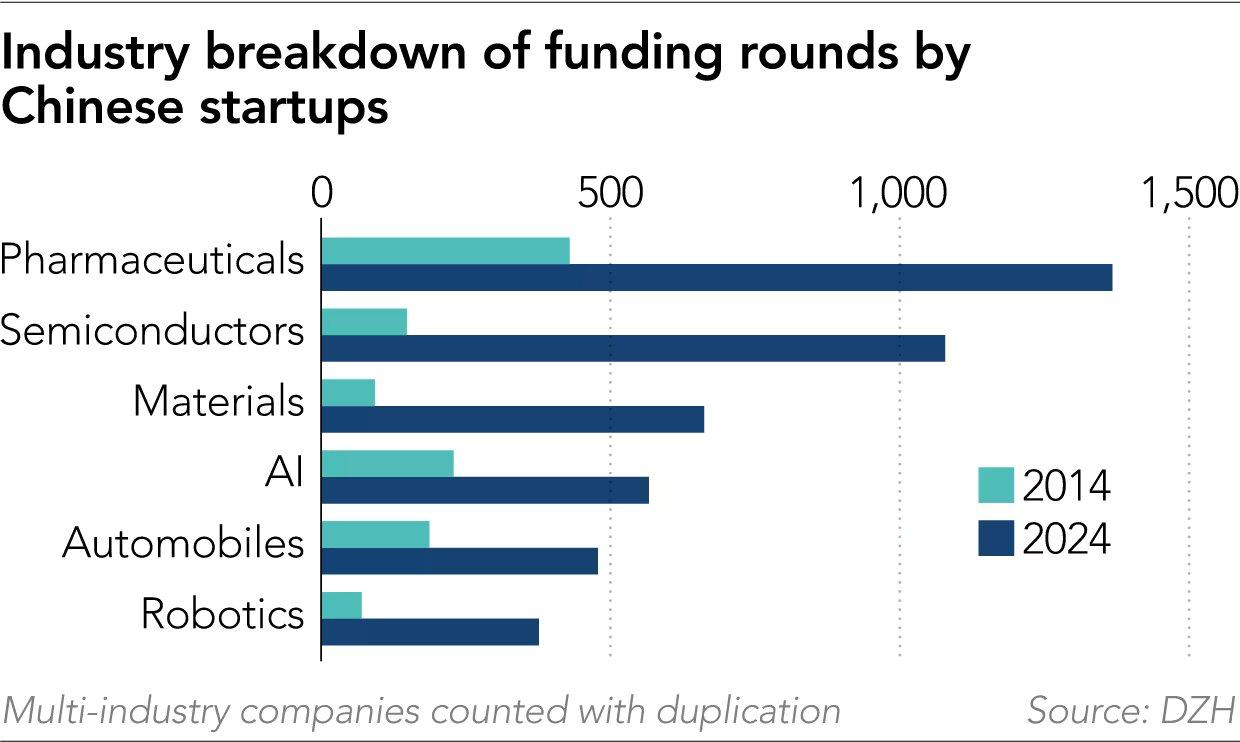

The winners under the new regime are predictable: sectors explicitly prioritized in the 14th Five-Year Plan and the Made in China 2025 roadmap.

- Pharmaceuticals & biotechnology now lead the pack in number of funding rounds, followed by semiconductors, advanced materials, AI, automobiles (especially EV and autonomous driving), and robotics (DZH Research, 2024 vs 2014 comparison).

- Between 2014 and 2024, the number of funding rounds for Chinese pharma/biotech startups exploded from ~400 to over 1,400 annually, while semiconductor deals grew from under 200 to nearly 1,200 (DZH).

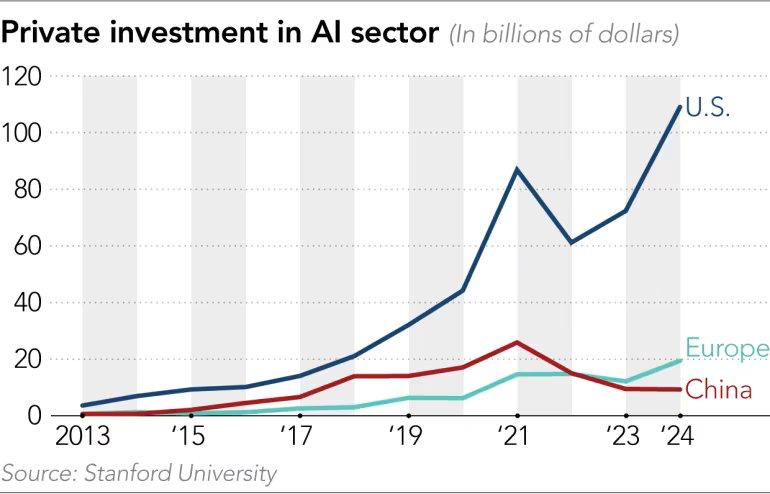

- AI-specific rounds, while still numerous, have shifted heavily toward government-backed investors; pure-play commercial AI startups saw foreign participation drop to under 12 % of total capital raised in 2024–2025 (Stanford AI Index 2025 preliminary data).

The rise of “politically significant unicorns” is the most visible outcome. Companies such as Baidu’s Apollo autonomous-driving unit, Cambricon (AI chips), Biren Technology (GPUs), and a new wave of large-language-model developers now routinely count central or provincial guidance funds among their cap tables.

The rise of “politically significant unicorns” is the most visible outcome. Companies such as Baidu’s Apollo autonomous-driving unit, Cambricon (AI chips), Biren Technology (GPUs), and a new wave of large-language-model developers now routinely count central or provincial guidance funds among their cap tables.

These entities — often structured as limited partners in RMB funds — bring not only capital but also regulatory fast-tracking, government procurement contracts, and protection from foreign takeover.

Meanwhile, global private investment in AI continues to concentrate in the United States. Stanford University’s latest data (AI Index 2025 preview) show U.S. private AI investment reaching approximately $110 billion in 2024, compared with a sharp decline in China’s dollar inflows and only modest growth in Europe. The gap has never been wider.

Beijing appears comfortable with the trade-off. Local government guidance funds, which raised a record 1.9 trillion yuan ($270 billion) in new commitments in 2023–2024 alone, have ample dry powder. State-backed chip fund “Big Fund” Phase III closed at 344 billion yuan in May 2024, and numerous provincial mega-funds targeting semiconductors and AI routinely exceed 100 billion yuan each.

Also read:

Also read:

- The Dawn of Agentic AI: Why Amazon's War on Perplexity's Comet Browser Signals a Seismic Shift in E-Commerce

- The Emerging Trend in the US: Skincare Brands for Kids

- China's Shadow Fishing Fleet: The Hidden Global Crisis

- What if ScanPST EXE does not Work?

For entrepreneurs, the new reality means accepting lower valuations in yuan terms, longer decision cycles, and sometimes explicit national-service obligations — but also greater certainty that their companies will not be crippled by sudden U.S. sanctions or forced divestments. As one Shanghai-based founder of an AI chip startup told the Financial Times in September 2025: “Two years ago we spent half our time pitching Sand Hill Road. Today, if a provincial guidance fund says yes, the round is done. The money is slower, but it doesn’t come with a kill switch.”

The decoupling of technology capital flows is now measurable in real time. What began as a gradual drift has accelerated into a structural break. Ten years ago, Chinese startups looked west for both money and validation. Today, the most ambitious founders increasingly look first to Beijing — and to the state entities that have replaced Silicon Valley as the dominant force in China’s innovation economy.