The global energy system is undergoing the fastest and most profound restructuring since the Industrial Revolution. According to the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook 2025, published in October, the next quarter-century will see an almost complete inversion of the world’s primary energy mix — a shift driven less by ideology than by simple economics, technological momentum, and the relentless Asian demand.

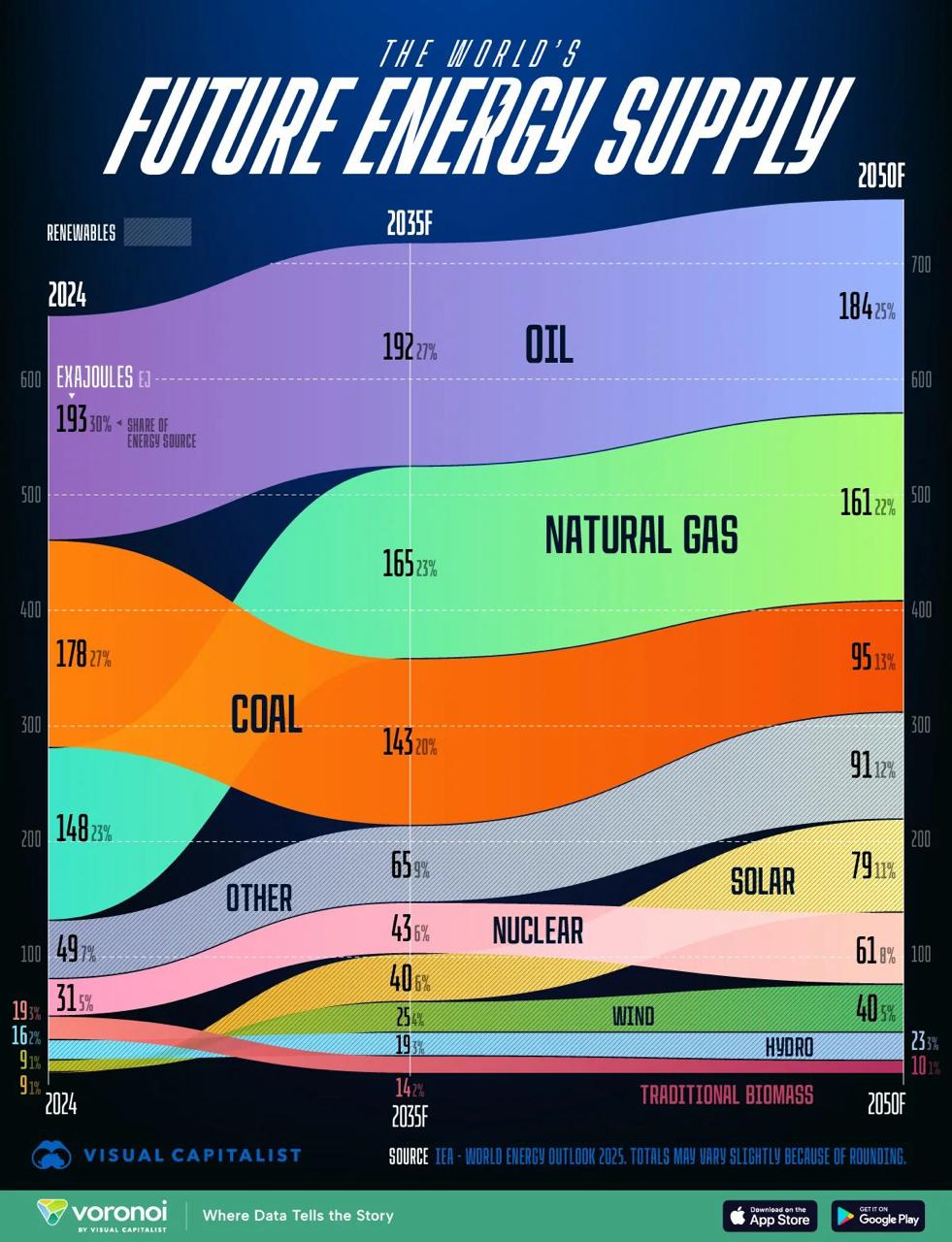

In 2024, fossil fuels still supply roughly 80 % of the world’s primary energy. By 2050, under the IEA’s Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS) — which reflects only currently announced government targets — that share collapses to just over 50 %. Renewables, including hydro, surge from 13 % today to 31 %, becoming the single largest contributor to incremental energy supply for the first time in history. The numbers are staggering: the world adds almost 9 000 TWh of new solar generation and 6 500 TWh of new wind between now and 2050 — equivalent to installing roughly three large nuclear reactors’ worth of clean capacity every single day for 25 years.

In 2024, fossil fuels still supply roughly 80 % of the world’s primary energy. By 2050, under the IEA’s Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS) — which reflects only currently announced government targets — that share collapses to just over 50 %. Renewables, including hydro, surge from 13 % today to 31 %, becoming the single largest contributor to incremental energy supply for the first time in history. The numbers are staggering: the world adds almost 9 000 TWh of new solar generation and 6 500 TWh of new wind between now and 2050 — equivalent to installing roughly three large nuclear reactors’ worth of clean capacity every single day for 25 years.

Solar leads the charge with the most explosive growth curve ever recorded for any energy technology. Its output jumps from 1 600 TWh in 2024 to nearly 14 000 TWh in 2050 — an 8.7-fold increase. Utility-scale plants in sun-soaked regions of China, India, the Middle East and the American Southwest, combined with an avalanche of behind-the-meter rooftop systems in Europe, Southeast Asia and Africa, drive the surge. By the late 2030s, the IEA expects the levelized cost of electricity from new solar in optimal locations to fall below US$10/MWh — cheaper than running an existing coal plant almost anywhere on Earth.

Wind power grows “only” five-fold, but from a much larger base, adding more absolute exajoules than any other source except solar. Offshore wind finally comes of age: fixed-bottom projects in the North Sea and East China Sea give way to massive floating turbines in deeper waters off California, Japan, Korea and Norway. By 2050, offshore wind alone supplies more electricity than all of today’s nuclear fleet combined.

Coal experiences the steepest absolute decline in human history. From a fuel that powered the 20th century — falls from 178 EJ (27 % of primary energy) in 2024 to 91 EJ (12 %) in 2050. China, still the world’s largest coal consumer, retires or repurposes more than 900 GW of coal capacity — equivalent to shutting down the entire U.S. coal fleet twice over. India’s coal demand peaks before 2030 and then enters a long plateau-to-decline trajectory as solar-plus-storage undercuts new coal economics even in Bihar and Jharkhand.

Coal experiences the steepest absolute decline in human history. From a fuel that powered the 20th century — falls from 178 EJ (27 % of primary energy) in 2024 to 91 EJ (12 %) in 2050. China, still the world’s largest coal consumer, retires or repurposes more than 900 GW of coal capacity — equivalent to shutting down the entire U.S. coal fleet twice over. India’s coal demand peaks before 2030 and then enters a long plateau-to-decline trajectory as solar-plus-storage undercuts new coal economics even in Bihar and Jharkhand.

Natural gas, long touted as the “bridge fuel,” proves to be more of a plateau than a bridge. Its absolute consumption rises modestly until the mid-2030s, largely to back up variable renewables and fuel Asian industrialization, then flattens and slowly declines after 2040. By 2050 it supplies 22 % of primary energy — still vital, but no longer growing.

Oil faces a slower but inexorable erosion. Demand peaks around 103 million barrels per day in the late 2020s (lower and earlier than most oil companies forecast) and drifts down to 75–80 mb/d by mid-century. Electric vehicles, now 18 % of global car sales in 2024, reach 85 % of new sales by 2035 and virtually 100 % by 2045 in Europe, China and parts of North America. Aviation and shipping remain stubborn holdouts, but sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) and green ammonia begin meaningful scale-up after 2035.

Nuclear power refuses to die, contrary to many obituaries written in the 2010s. Global nuclear output almost doubles from 31 EJ in 2024 to 61 EJ in 2050, led by new builds in China (adding ~150 GW), India (~50 GW), and a surprising late-decade revival in Europe and North America driven by small modular reactors (SMRs) and data-center demand for carbon-free baseload. France, South Korea and the UAE extend existing fleets; the UK finally finishes Hinkley Point C and Sizewell C; while the U.S. sees its first new large reactor in decades (Vogtle units 3 & 4) joined by NuScale, GE-Hitachi and TerraPower deployments from the early 2030s onward.

Hydrogen and its derivatives emerge as the wildcard. Electrolysis capacity explodes from <1 GW today to over 800 GW by 2050, producing 80 million tonnes of green hydrogen annually — enough to decarbonize nearly all ammonia production, half of steelmaking, and significant shares of heavy trucking and shipping.

Hydrogen and its derivatives emerge as the wildcard. Electrolysis capacity explodes from <1 GW today to over 800 GW by 2050, producing 80 million tonnes of green hydrogen annually — enough to decarbonize nearly all ammonia production, half of steelmaking, and significant shares of heavy trucking and shipping.

The “Other Renewables” category — geothermal, modern bioenergy, marine, and concentrated solar power — grows from a rounding error to a respectable 65 EJ, roughly the size of today’s entire natural-gas industry in the United States.

Enhanced geothermal systems finally crack the code in Japan, Indonesia, East Africa and the western U.S., while sustainable biomass with carbon capture (BECCS) delivers the world’s first meaningful negative emissions at scale in Brazil, Scandinavia and the American Midwest.

Perhaps most remarkably, the entire transformation happens while global primary energy demand continues rising — from ~620 EJ today to ~750 EJ in 2050 — driven by population growth, electrification, and hundreds of millions of new middle-class consumers in Africa and South Asia. Clean energy doesn’t just replace fossil fuels; it overwhelmingly powers new demand.

The result is an energy world almost unrecognizable from today’s: solar and wind jointly supply more primary energy than oil ever did at its peak; coal becomes a niche fuel like fuel-oil is now; nuclear quietly doubles; and electricity jumps from 20 % to over 50 % of final energy consumption.

Also read:

Also read:

- The White House's Digital Pillory: Trump's Media Blacklist Goes Live, with CBS News in the Crosshairs

- AI's Power Thirst: A Quadrupled Demand That Could Eclipse Entire Nations

- BritCard Blues: Britain's Digital ID Dream Sparks a 2.9 Million-Strong Orwellian Nightmare

The IEA’s central scenario is no green utopia — it assumes no new climate policies beyond those already on the books in 2025. If nations actually meet their net-zero pledges (the Announced Pledges Scenario), the fossil share falls below 30 % and renewables exceed 50 %. Either way, the direction is unmistakable: the age of fossil dominance is ending not with a bang, but with a steady, market-driven, technology-fueled flip of the entire energy stack. By mid-century, humanity will derive more energy from the sun in a single year than it extracted from coal across the entire 20th century. The great energy transition isn’t coming — it’s already here, quietly and irreversibly, here.